Migrating up the tech ladder

Migrating birds

Migrating birds

Every now and then I’ll be leading a team of engineers, and someone will ask something along the lines of “How did you learn how to do that?”. I rarely have that good an answer, but recently I realised there is a pattern to how I gained a lot of the technical knowledge I do have — I’ve taken part in a lot of migration projects.

So the TLDR; from this article for anyone seeking to turbocharge their technical knowledge is:

If there’s a big, complex, scary, maybe boring-sounding migration coming up, volunteer for it. It’s not glamorous, eye-catching work, but you will learn a lot from the experience.

To illustrate what I mean, here’s my history of doing migrations in 4 chapters. Having read it a few times to check for typos, I’m struck (even more than I expected to be) by how closely it mirrors the kind of skills you have to acquire as you progress from engineer, to senior to and then to principal.

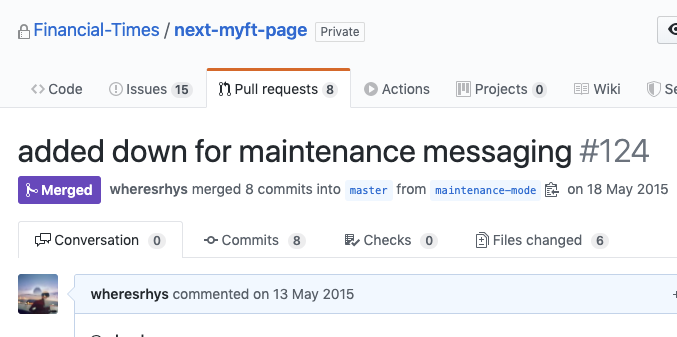

1. MyFT

MyFT is now one of the most successful features of FT.com. It started off as an experiment back in the bootcamp days of the website rebuild. After a few months, those leading the project saw that it had potential, and myself and Arjun formed a small team to refine it.

A few weeks in, we realised that the data model we had, stored in the somewhat inflexible DynamoDB, did not fit well with where we wanted to take it, so we decided we had to move all the data into a different structure. I can’t remember exactly how we broke down the work, but I ended up writing the migration script.

A migration script, for the uninitiated, is an often ugly — it’s only going to be used once — piece of code that will read all the data from one store and write it to another, carrying out any transformations necessary. The sensible way to run such a script is to migrate from a test database to a test database, then from the old one to a test one, and then from the old one to the new one — making sure that you have backups and a rollback plan. Being a novice, I did none of these things. We turned off the application, ran the script and — luckily — it all still worked (though we may have needed to give it a few nudges).

Not so long after, we decided to remodel the data again, and migrated to yet another data store — neo4j graph database — and this time the task didn’t seem so frightening. I had some code snippets I could reuse from the previous migration, and I’d learned what parts of the previous migration — the lack of a backout plan for instance — were stressful, so I was able to mitigate them by planning more carefully. As I recall, it went without a hitch, with only a little planned downtime.

There was a sting in the tail a few months on when we discovered that all the indexes on the new database had gone missing. Recovering from that wasn’t fun (a rare occasion when I’ve worked really late), but the skills I’d learned from the first two migrations meant I could deal with it relatively calmly and analytically.

So that’s the first thing I got from migrations — I lost my fear of databases and, more generally, fear of technologies I don’t consider myself an expert in. I’m still not a DB expert, but I’ve gained a lot of common sense knowledge of how to work with them.

2. n-ui

n-ui was the front end templating, asset loading and web page bootstrapping behemoth shared by all ft.com’s user facing microservices. While I still have fond memories of working on it, and some residual pride in what it was capable of, it’s fair to say that it was a monster that was difficult to understand and hard to work with. This was still true at version 7, but nothing compared to the horrors it contained at versions 1 & 2.

After hearing the generally negative reviews from the engineering team, I worked on rolling back some of its worst unintuitive excesses in a sandboxed environment. But by the time the new, slightly simplified version 3 was ready to be adopted, n-ui was deeply embedded in around 15 applications. Upgrading every one of them would be a mammoth task; I was going to need some help.

So I booked a large meeting room, invited 10 engineers or so, bought a range of biscuits from our local supermarket, and we all sat down to code. I’d done some preparation, writing a step by step guide to what would need changing in a typical application, but very soon voices piped up stating that things weren’t working as predicted (the ft.com frontend is built out of a lot of front end components, and updating the cascade can be full of surprises).

By the end of the day a respectable number of applications had pull requests ready to merge, and for all the others we had a good understanding of how to overcome the obstacles we’d uncovered. Everyone had enjoyed the experience too; there was a real hack-day vibe in that room, and the sense of achievement at being tantalisingly close to getting rid of some coding patterns that everybody despised was immense.

This was also the first time I’d set up a technical project by myself and arranged for a number of people to work towards a moderately time-pressured goal. I learned a lot about how to coordinate people to work as a team, and how to help the team adapt to unexpected events. This would serve me well as I approached the next migration, which was just around the corner.

3. CAPI2

The Financial Times Content API (or CAPI for short) has had two major versions — CAPI1 and CAPI2. In an ideal world, CAPI2 would have provided everything we needed to build ft.com before the project began, but it was not to be, so we built it mainly on top of CAPI1.

As CAPI2’s content model gained feature parity with CAPI1 (i.e. it could represent all the elements of a typical story written in the newsroom), we were ready to move off CAPI1, but for one snag: CAPI2 had a completely different metadata system to CAPI1. They both annotated articles with pieces of metadata, but between CAPI1 and CAPI2 the ids were different, the content of each item of metadata was different, and the relationships between the content and the metadata were described differently. The APIs that allowed interacting with this metadata also differed in subtle but annoying ways.

This CAPI1 metadata was being used all over the place, from urls for index pages to allowing users to follow topics they were interested in in myFT. Migrating to CAPI2 without breaking any of the features that relied on CAPI1 was a huge undertaking. As my boss Sarah is fond of saying, we had to change horses midstream. There was also a lot of time pressure, as decommissioning the complex and expensive to run CAPI1 infrastructure was blocked by ft.com’s usage of it, and this risked derailing other aspects of the decom project.

I won’t go through the details (there are too many to remember), but the skills I’d learned from previous migrations were invaluable. I had to reason about the impact and dependencies of a wide range of changes (including having plans to rollback any that failed), coordinate the work of various teams, and still get stuck in with practical engineering work, focusing my effort on the parts of the project that seemed most at risk of falling behind. I had to communicate regularly with stakeholders and people in other teams who were working on other early stages of the CAPI1 switch off, making sure I was clear and open about what was on track and what wasn’t. When things weren’t working out as planned, or achieving the ideal solution was too much effort, I had to make the call to go for Plan B, and this often meant negotiating with other teams to get them on board with the new approach.

What I’ve just described is my learning to be a technical leader. I might have waited a long time for another opportunity to get that experience if the CAPI1 migration hadn’t come along when it did. When we hit the final switch to turn off our API calls to CAPI1, we all gathered around my laptop and listened to the theme to Chariots of Fire, which felt like an appropriate way to end it.

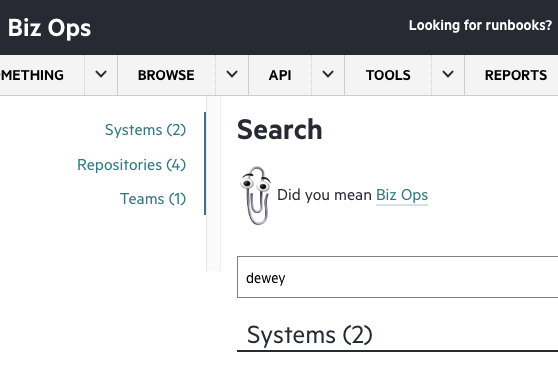

4. Dewey

And on to my present job, in the Reliability Engineering team. One of the things we do is try to build up a picture of all the tech we run and how it relates to the business’s activities. Over the years there have been several attempts to model this information. The most recent but one was called Dewey, a Postgres database with a number of user interfaces and consumers hanging off it, with varying degrees of coupling.

When I arrived, the migration to its successor — Biz Ops — was already at the advanced prototype stage as far as the data model was concerned, but had barely begun when it came to working out how to replace the Dewey APIs, admin screens, update streams and a number of applications that depended on them. The ambitious goal was to migrate with zero downtime.

Superficially, the migration was less challenging than CAPI1 — lower stakes, and without much time pressure — but what made it more difficult was that this was a source of data that we both wrote to and read from, and maintaining its consistency was entirely our responsibility. Its users were also internal, and we had the reputation of our fledgling team to think of; we didn’t want to start off with a car crash project that degraded other teams’ ability to do their jobs.

This was the first time I’d been responsible for a migration that wasn’t some hidden technical detail. This time, we expected people to notice the change, and hopefully to like it. As a team that only has technical staff, I had to product and project manage. This meant attempting to understand our users enough to make the right decisions about which disruptions would be acceptable. To this day I’m not convinced that the migration process was the most sensible — continuously syncing updates from the old to the new datastore, and gradually killing off edit functionality in the old applications — but it did give us the ability to get early feedback before the new applications were complete (a practice I highly recommend). While there were some trying episodes where the new product wasn’t meeting users’ expectations, it’s far better to address these when things are still fluid, rather than when the project is supposed to be finished.

The migration, to the untrained eye, ended with one last script to fix some inaccurately mapped cost attribution data, and then my colleague Laura’s son clicked the merge button on the final PR. What followed for our team was a tedious decommissioning job, and, soon after, migrating the new stack in its entirety into a dedicated AWS account (difficult while it was still hooked up to updates from the old applications).

A year on from the switch over day, we have a product that is still growing in use, and a team that has a reputation for building useful, high quality tools for our users.

Conclusion

migrating the new stack in its entirety into a dedicated AWS account

I would never have imagined, just a few years ago, that I’d be saying that so nonchalantly. It’s largely working on migrations over the years that has given me the technical, planning, communication and leadership skills that mean I see complex technical projects as challenges, but not as insurmountable mountains to climb.

But what are the main things I’ve learned from throwing myself into migration projects

A greater awareness of the full software lifecycle

When implementing a new feature everyone is in a forward thinking mindset — how do we get X to work, how do we add this widget, etc., and it’s rare, in a mature DevOps project, that changes cannot be undone by clicking a button or reverting a PR. But backing out of something that is deeply embedded in your tech requires a lot more thought and planning. Once learned on a migration project, these aptitudes can be used again and again. They are particularly useful when evaluating the pros of cons when you introduce libraries, dependencies etc. into projects.

How to work with difficult, legacy codebases

Legacy projects are never the nicest thing to work on, but it’s an unfortunate fact that, given enough time, every application becomes something that people are afraid to touch. Migration is a great way to get comfortable working in codebases you don’t know and don’t fully understand, gleaning just enough knowledge to get you through, and ending with a positive achievement; you will have decommissioned at least some of the horrible codebase you were stuck working in.

Directing other people’s work

Without becoming a full on, permanent tech lead, migrations can give you an opportunity to shepherd people from across different teams and disciplines in pursuit of a shared goal. You will gain the negotiation skills needed to get your boring migration prioritised above more exciting projects, and gain confidence in the validity of your views as — yes — a technical leader.

… and lots more besides.

So give it a go — let boring, under the radar, thankless migrations be your route to becoming a better engineer. We’re always looking for talent so please have a look at our Product and Technology microsite for more information about our teams.

(Also check out my colleague Maggie’s great post about her recent migration story, replacing n-ui with something much, much better)

Yaffle